The Nile and her (dis)tributaries

Just like a river may have a main stream from and into which distributaries and tributaries flow respectively, a development workflow may have a main line and branches that serve as points of divergence from the mainline. This gives a contributor a separate channel to make changes without worrying about messing up the main line of development. Once content with the changes, you can merge them back to the main line.

Branching defined; technical perspective

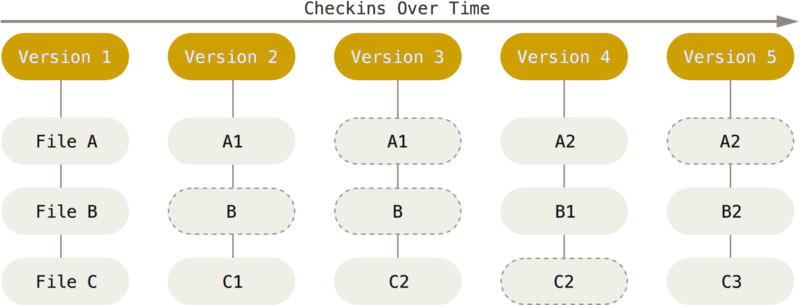

Key to understanding how Git does branching is a close examination of how Git really stores it data. Instead of storing a series of sets of changes or deltas, data is stored as a series of snapshots.

Storing data as snapshots of a project over time. Adapted from https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-Git-Basics

When you make a commit, Git stores a commit object that contains:

- A pointer to the snapshot of the content staged, the author and object metadata (data of data)

- Zero or more pointers to the commit(s) that were the direct parents of this commit; zero parents for the first commit, one parent for a normal commit, and multiple parents for a commit that resulted from a merge of multiple branches.

Picture this. You have three files all of which you stage and commit. Staging the files:

- checksums (stores a hexadecimal representation) each one,

- stores that version (known as blob) of the file in the Git repository, and

- adds that checksum to the staging area:

git add README test.rb LICENSE

git commit -m 'initial commit of my project'

Running git commit :

- checksums all project directories and stores them as as tree _objects in the _Git repository,

- creates a _commit _object that has the metadata to the root project _tree _object (mentioned above) so it can recreate that snapshot when needed, e.g., during a

git revert